Hepatitis B virus (HBV), one of mankind’s most important pathogens, infects about 2 billion people worldwide, and more than 500 million individuals are life-long carriers of the virus; with most in Asia. HBV causes acute and chronic cirrhosis, as well as hepatocellular carcinoma. In point of fact, HBV is the 10th leading cause of death in the world! The serendipitous discovery of HBV, and the development of the first HBV vaccine, happened as follows. [See Note 1 for a brief review of the remarkable HBV replication strategy].

In the early 1940’s, during World War II, British doctor, F. O. MacCallum, was the first to suggest that an infectious agent might cause hepatitis. MacCallum was assigned to produce a yellow fever vaccine for British soldiers. That was how he happened to notice that soldiers tended to come down with hepatitis a few months after receiving the yellow fever vaccine.

It was fortunate that MacCallum also knew of hepatitis cases in children who received inoculations of serum from patients convalescing from measles and mumps (a means of protection against those viruses before vaccines were available), and of hepatitis cases in blood transfusion recipients, and of cases following treatments with unsterilized reused syringes.

To explain these coincidences, MacCallum hypothesized that hepatitis might be transmitted by a factor in human blood. And, since hepatitis could be transmitted by inoculation with serum that had been filtered, MacCallum proposed that the hepatitis factor might be a virus. [In 1947 MacCallum reported that hepatitis could be spread by food and water that had been contaminated with fecal material, as well as by blood. He coined the term hepatitis A for the form of the disease spread by food and water, and hepatitis B for the form transmitted via blood.] See Aside 1.

[Aside 1: The following episode, described in MacCallum’s own words (1), occurred in England during World War II: “One day in 1942, I received a message to go to Whitehall to see one of the senior medical advisers and when I arrived I was asked ‘What is this yellow fever vaccine and how dangerous is it?’ After explaining its constitution and the possibility of a mild reaction four to five days after inoculation, I was told that the Cabinet was at that moment debating whether or not Mr. Churchill should be allowed to go to Moscow, which he wished to do in a few days’ time. The yellow fever vaccine was theoretically essential before he could fly through the Middle East, but I explained that no antibody would be produced before seven to ten days so that there would be little point in giving the vaccine. It was finally decided that the vaccine would not be used, and the administrators would take care of the situation. Several months later I received an irate call from the Director of Medical Services of the RAF, who had been inoculated with the same batch of vaccine which would have been used for Mr. Churchill, and was informed that the D. G. had spent a very mouldy Christmas with hepatitis about 66 days after his inoculation…I will leave it to you to speculate on what might possibly have been the effect on the liver of our most famous statesman and our ultimate fate if he had received the icterogenic vaccine.”]

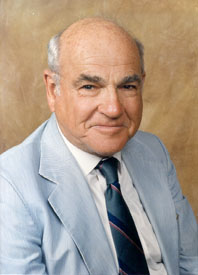

With the advent of cell culture in the 1950s, researchers hoped that a hepatitis agent might soon be cultivated in vitro. Nonetheless, HBV was not discovered until 1966. What’s more, the discovery did not involve growing the virus in cell culture. And, reminiscent of the case of MacCallum above, the discovery was made by a researcher, Baruch S. Blumberg, who was not even working on hepatitis. Rather, Blumberg was interested in why individuals varied in their susceptibilities to various illnesses.

Blumberg sought to answer that question by identifying possibly relevant genetic differences between population groups, which, in the pre-molecular biology era, might be revealed by differences in their blood proteins. Thus, in the early 1950s, Blumberg, then working at the NIH, began collecting a panel of blood samples from diverse populations throughout the world.

Blumberg looked for serum protein variations (i.e., serum protein polymorphisms) by asking if sera from multiply-transfused individuals (defined by Blumberg as persons who received 25 units of blood or more) might contain antibodies that reacted with proteins in the serum samples of his panel. His rational, in his own words, was as follows: “We decided to test the hypothesis that patients who received large numbers of transfusions might develop antibodies against one or more of the polymorphic serum proteins (either known or unknown) which they themselves had not inherited, but which the blood donors had (2).” In other words, patients who received multiple transfusions were more likely than others to have antibodies against polymorphic serum proteins in donor blood, and those antibodies might also react with polymorphic serum proteins in the samples from his panel. See Aside 2.

[Aside 2: Blumberg used the Ouchterlony double-diffusion agar gel technique in these experiments. Serum samples to be tested against each other were placed in opposite wells of a gel. The proteins they contained could then diffuse through the gel. Antigen-antibody complexes that formed between the two samples appeared as white lines in the gel.]

Hemophilia and leukemia patients were well-represented in Blumberg’s collection of serum samples from multiply-transfused individuals. And, a serendipitous aspect of Blumberg’s experimental approach was that he used these samples to probe for serum protein polymorphisms in samples from geographically diverse populations. Thus it happened that Blumberg detected a cross-reaction between a New York hemophilia patient’s serum and a serum sample from an Australian aborigine. But what could these two individuals have had in common that might have triggered the cross-reaction?

His curiosity thus aroused, Blumberg and collaborator, Harvey Alter, of the NIH Blood Bank, tested the hemophilia patient’s serum against thousands of other serum samples. Blumberg and Alter may have been surprised to find that whatever the antigen in the Aborigine’s serum was that reacted with the hemophilia patient’s serum, reactivity against that antigen was common (one in ten) in leukemia patients, but rare (one in 1,000) in normal individuals. In any case, because the antigen was first identified in an Australian aborigine, it was termed the Australia antigen.

Bear in mind that Blumberg’s original purpose was to explain why individuals differed in their susceptibilities to various illnesses. Thus, Blumberg at first believed that he detected an inherited blood-protein that predisposes people to leukemia. However, additional experiments showed that the antigen was more common in older individuals than in younger ones; a finding more consistent with the possibility that the antigen might be associated with an infectious agent.

Blumberg’s first clue that the Australia antigen might be associated with hepatitis came to light when he tested serum samples from a 12-year old boy with Down syndrome. The first time that the boy was tested for the Australia antigen, he was negative. However, several months later, when retested, the boy was positive. Moreover, sometime during that interim, the boy also developed hepatitis.

Blumberg, and other researchers, carried out additional experiments, which confirmed that the Australia antigen indeed associated with hepatitis. In addition, the antigen was more frequently detected in hepatitis sufferers than in individuals with other liver diseases. Thus, the Australia antigen was a marker of hepatitis in particular and not of liver pathology in general. See Aside 3.

[Aside 3: Blumberg had a personal reason motivating him to identify the cause of hepatitis. His technician (later Dr. Barbara Werner) became ill with hepatitis, which she almost certainly acquired in the laboratory. Fortunately, she underwent a complete recovery.]

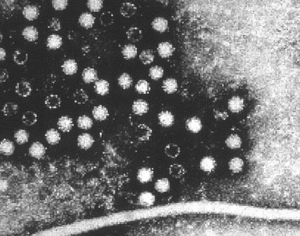

In 1970, British pathologist David Dane and colleagues at Middlesex Hospital in London, and K. E. Anderson and colleagues in New York, provided corroborating evidence that hepatitis is an infectious disease. Using electron microscopy, they observed 42-nm “virus-like particles” in the sera of patients who were positive for the Australia antigen. In addition, they saw these same particles in liver cells of patients with hepatitis.

What then is the Australia antigen? Actually, it is the surface protein of the 42-nm HBV particles; now known as the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Since HBV particles per se were described for the first time by David Dane, they are sometimes referred to as Dane particles.

Now we can explain Blumberg’s early finding, that individuals who received multiple transfusions (e.g., leukemia and hemophilia patients) were more likely than the general population to have antibodies against the Australia antigen. Those individuals were more likely than the general population to have received donated blood and, thus, were more likely to have been recipients of blood contaminated with HBV. At that time, a large percentage of the blood supply came from paid donors, at least some of whom were syringe-sharing, intravenous drug abusers and, consequently, more likely than most to be HBV carriers. In 1972 it became law in the United States that all donated blood be screened for HBV. See Note 2.

But it was important to protect all people from HBV; not just transfusion recipients. In 1968, Blumberg, now at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, and collaborator Irving Millman, hypothesized that HBsAg might provoke an immune response that would protect people against HBV and, consequently, that a vaccine could be made using HBsAg purified from the blood of HBV carriers. In Blumberg’s own words: “Irving Millman and I applied separation techniques for isolating and purifying the surface antigen and proposed using this material as a vaccine. To our knowledge, this was a unique approach to the production of a vaccine; that is, obtaining the immunizing antigen directly from the blood of human carriers of the virus (1).” The Fox Chase Cancer Center filed a patent for the process in 1969.

Blumberg was willing to share his method and the patent with any pharmaceutical company willing to develop an HBV vaccine for widespread use. Nonetheless, the scientific establishment was somewhat slow to accept his experimental findings and his proposal for making the vaccine. Then, in 1971, Merck accepted a license from Fox Chase to develop the vaccine. In 1982, after more years of research and testing, Maurice Hillman (3) and colleagues at Merck turned out the first commercial HBV vaccine (“Heptavax”). Producing an HBV vaccine, without having to cultivate the virus in vitro, was considered one of the major medical achievements of the day. See Notes 3 and 4.

The consequences of Blumberg’s vaccine were immediate and striking. For instance, in China the rate of chronic HBV infection among children fell from 15% to around 1% in less than a decade. And, in the United States, and in many other countries, post-transfusion hepatitis B was nearly eradicated.

Moreover, Blumberg’s HBV vaccine was, in a real sense, the world’s first anti-cancer vaccine since it prevented HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma, which accounts for 80% of all liver cancer; the 9th leading cause of death. Jonathan Chernoff (the scientific director of the Fox Chase Cancer Center, where Blumberg spent most of his professional life) stated: “I think it’s fair to say that Barry (Blumberg) prevented more cancer deaths than any person who’s ever lived (4).”

In 1976 Blumberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “discoveries concerning new mechanisms for the origin and dissemination of infectious diseases.” He shared the award with Carlton Gajdusek, who won his portion for discoveries regarding the epidemiology of kuru (5). See Note 5.

Blumberg claimed that saving lives was the whole point of his career. “This is what drew me to medicine. There is, in Jewish thought, this idea that if you save a single life, you save the whole world, and that affected me (7).” See Aside 4.

[Aside 4: Blumberg received his elementary school education at an orthodox yeshiva in Brooklyn, and he attended weekly Talmud discussion classes until his death. Interestingly, Blumberg graduated from Far Rockaway High School in Queens, N.Y.; also the alma mater of fellow Nobel laureates, physicists Burton Richter and Richard Feynman.]

As we’ve seen, Blumberg’s landmark discovery of HBV sprang from a basic study of human genetic polymorphisms. In Blumberg’s own words, “… it is clear that I could not have planned the investigation at its beginning to find the cause of hepatitis B. This experience does not encourage an approach to basic research which is based exclusively on specific-goal-directed programs for the solution of biological problems (1).”

Saul Krugman (Note 4) had this to say about Blumberg’s discovery: “It is well known that Blumberg’s study that led to the discovery of Australia antigen was not designed to discover the causative agent of type B hepatitis. If he had included this objective in his grant application, the study section would have considered him either naïve or out of his mind. Yet the chance inclusion of one serum specimen from an Australian aborigine in a panel of 24 sera that was used in his study of polymorphisms in serum proteins…led to detection of an antigen that subsequently proved to be the hepatitis B surface antigen (1).” See Note 6.

In 1999, Blumberg’s scientific career took a rather curious turn when he accepted an appointment by NASA administrator, Dan Goldin, to head the NASA Astrobiology Institute. There, Blumberg helped to establish NASA’s search for extraterrestrial life. Blumberg also served on the board of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

Blumberg passed away on April 5, 2011, at 85 years of age.

Notes:

[Note 1: HBV is the prototype virus for the hepadnavirus family, which displays the most remarkable, and perhaps bizarre, viral replication strategy known. In brief, in the cell nucleus, the cellular RNA polymerase II enzyme transcribes the hepadnavirus circular, double-stranded DNA genome, thereby generating several distinct species of viral RNA transcripts, all of which are exported to the cytoplasm. The largest of these viral transcripts is the pregenomic RNA; a transcript of the entire circular viral DNA genome, as well as an additional terminal redundant sequence. Remarkably, the pregenomic RNA is then packaged in nascent virus capsids, within which it is reverse transcribed by a virus-encoded reverse transcriptase activity, thereby becoming an encapsulated progeny hepadnavirus double-stranded DNA genome. Thus, reverse transcription is a crucial step in the replication cycle of the hepadnaviruses, as it is in the case of the retroviruses. But, while the retroviruses replicate their RNA genomes via a DNA intermediate, the hepadnaviruses replicate their DNA genomes via an RNA intermediate.]

[Note 2: The highly sensitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) technique, developed by Rosalyn Yallow and Solomon Berson, is the basis for the test that screens the blood supply for the Australia antigen. The story behind this assay is worthy of note here because it is yet another example of serendipity in the progress of science. In brief, Yallow and Berson sought to develop an assay to measure insulin levels in diabetics. Towards that end, they happened to find that radioactively-labeled insulin disappeared more slowly from the blood samples of people previously given an injection of insulin than from the blood samples of untreated patients. That observation led them to conclude that the treated patients had earlier generated an insulin-binding antibody. And, from that premise they hit upon the RIA procedure. Using their insulin test as an example, they would add increasing amounts of an unlabelled insulin sample to a known amount of antibody bound to radioactively labeled insulin. They would then measure the amount label displaced from the antibody, from which they could calculate the amount of unlabelled insulin in the test sample. Their procedure has since been applied to hundreds of other substances. RIA is simpler to carry out and also about 1,000-fold more sensitive than the double-diffusion agar gel procedure that Blumberg used to identify the Australia antigen. Yallow and Berson refused to patent their RIA procedure, despite its huge commercial value. Yallow received a share of the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her role in its development. Berson, died in 1972 and did not share in the award.]

[Note 3: Making Heptavax directly from the blood of human HBV carriers was somewhat hindered because it required a continuing and uncertain supply of suitable donor blood. Moreover, there was concern that even after purifying the HBsAg, and treating it with formalin to inactivate any infectivity, the vaccine might yet contain other live dangerous viruses. Concern increased in the early 1980s with the emergence of HIV/AIDS, since much of the HBV-infected serum came from donors who later developed AIDS. Thus, in 1990 Heptavax was replaced in the United States by a safer genetically engineered (i.e., DNA recombinant) HBV vaccine, which contained no virus whatsoever. That vaccine was the first to be made using recombinant DNA technology. Moreover, it was yet another instance in which Hilleman played a key role in the development of a vaccine (3).]

[Note 4: In 1971, Saul Krugman, working at NYU, was actually the first researcher to make a “vaccine” against HBV. Krugman’s accomplishment began as a straightforward inquiry into whether heat (boiling) might kill HAV (see Note 5). Finding that it did, Krugman repeated his experiments; this time to determine whether boiling might likewise kill HBV in the serum of HBV carriers. As Krugman expected, boiling indeed destroyed HBV infectivity. But, to his surprise, while the heated serum was no longer infectious, it did induce incomplete, but statistically significant protection against challenge with live HBV. Krugman considers his “vaccine” discovery, like Blumberg’s discovery of HBV, to have resulted from “pure serendipity” (1).

Krugman could not answer whether HBsAg per se in his crude vaccine induced immunity. However, Hilleman, in 1975, using purified HBsAg, as per Blumberg’s concept, showed that HBsAg indeed induced immunity against an intravenous challenge with HBV.

Krugman also carried out key studies on the epidemiology of hepatitis, demonstrating that “infectious” (type A) hepatitis is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, while the more serious “serum” (type B) hepatitis is transmitted by blood and sexual contact.

Krugman reputation was somewhat tarnished because he used institutionalized disabled children as test subjects in the experiments that led to his vaccine. While that practice astonishes us today, it was not unheard-of in the day. In any event, it did not prevent Krugman’s election in 1972 as president of the American Pediatric Society, or his 1983 Lasker Public Service Award.]

[Note 5: Gajdusek’s reputation was later sullied when he was convicted of child molestation (5).]

[Note 6: In 1973 and 1974, research groups led by Stephen Feinstone and Maurice Hilleman (3) discovered hepatitis A virus (HAV), a picornavirus.

After the discoveries of HAV and HBV, it became clear that blood samples cleared of HAV and HBV could still transmit hepatitis. In 1983 Mikhail Balayan identified a virus, now known a hepatitis E virus (the prototype of a new family of RNA viruses), as the cause of a non-A, non-B infectious hepatitis (6).

In 1989, a mysterious non-A, non-B hepatitis agent, now known as hepatitis C virus (a flavivirus), was identified by a team of molecular biologists using the cutting-edge molecular biology techniques of the day (8).]

References:

- Krugman, S. 1976. Viral Hepatitis: Overview and Historical Perspectives. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 49:199-203.

- Blumberg, B, Australia Antigen and the Biology of Hepatitis B, Nobel Lecture, December 13, 1976.

- Maurice Hilleman: Unsung Giant of Vaccinology, Posted on the blog April 24, 20143.

- Emma Brown (6 April 2011). “Nobelist Baruch Blumberg, who discovered hepatitis B, dies at 85”. The Washington Post.

- Carlton Gajdusek, Kuru, and Cannibalism, Posted on the blog April 6, 2015.

- Mikhail Balayan and the Bizarre Discovery of Hepatitis E Virus, Posted on the blog May 3, 2016.

- Segelken, H. Roger (6 April 2011). “Baruch Blumberg, Who Discovered and Tackled Hepatitis B, Dies at 85”. New York Times.

- Choo, Q. L., G. Kuo, A.J. Weiner, L.R. Overby, D.W. Bradley, and M. Houghton. 1989. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244:359-362.